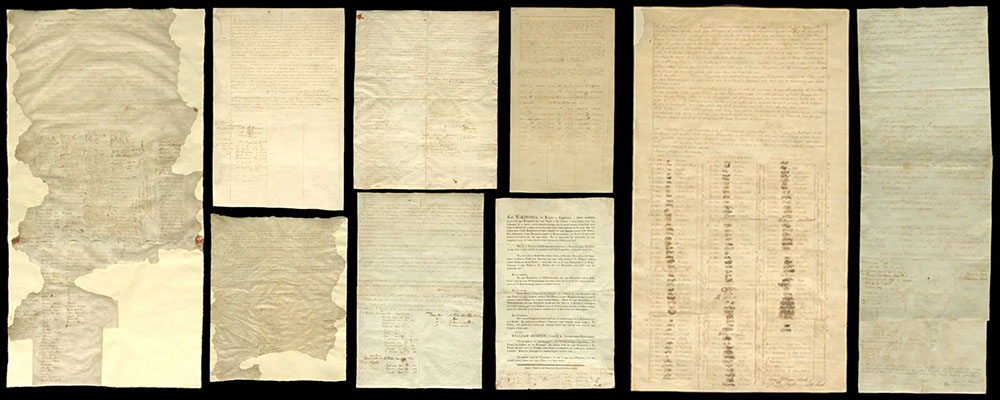

When Matt and I were here 20 years ago, we did all the tourist things but that was a very long time ago. So we are going back to places we visited before. This time it was the Te Papa Tongarewa Museum. The museum houses art and artifacts from New Zealand’s history. For me, the most interesting exhibit concerns the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi, in which the British obtained a cession of all land in Aotearoa from the Maori, the indigenous tribes on the islands. This is considered the founding document of New Zealand.

To obtain consent, the British did a lot of talking and explaining. The Maori did not rely on writing but relied on oral statements as binding. When the terms were converted to writing, the interpretation and translation were not the same as what the tribes understood. The majority of the Tribes signed based on the oral promises and explanations made, not on the document. Notably, not all tribes signed, but in the end, the British treated all tribes as if they had.

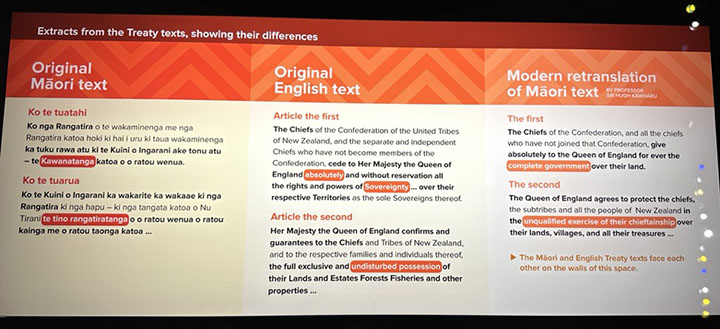

With surprising honesty, the exhibit explains that the British version of the Treaty and the Maori translation of the Treaty are not the same. The words used by the English in explaining the agreement to the Maori were interpreted differently when put into writing.

As was true in every other country they visited, the British intended to assert their sovereignty over the land and they sought a cession of sovereignty from the tribes. This was a foreign concept in Aotearoa, which was governed by individual tribes. There was no central government. Even so, the British version of the Treaty states the Maori ceded their sovereignty to the Crown. In fact, Maori understood in their language, that they were giving up governance over the land generally, but they would be free to govern themselves, their affairs and their “treasures,” meaning not just land but intangibles.

The British version gives the Maori the right to enjoy their land, forests, fish, and estates, but the Crown retained the full right to control the land in what is known as the right of preemption. The right of preemption, which was also used by the British in the United States, means that tribes may occupy the land, but the European Crown holds underlying authority and is in control of the purchase and sale of lands. In other words, the Crown has preempted the right of the Maori to control their land and the potential for foreign interests to buy it. Unless the Crown approves, the Maori cannot sell their land to anyone. This was how the British kept other countries at bay. It would be illegal under international law for the French to try to buy up property to challenge the Brits if preemption was granted.

But, as in the U.S., the necessity of obtaining consent from the Crown became an issue with settlers who wanted the land. So the New Zealand government started buying up land to dole out to settlers. They also worked to assimilate the Maori into society, which naturally led to the Maori being marginalized. War broke out pretty quickly (1860-1870), and the British used that war as an excuse to confiscate more land from the tribes. The promise to the Maori that they be permitted to govern their own affairs, i.e., to continue their tribal existence, was never met.

I could go on. The history of New Zealand mirrors the U.S. history of Indian wars, taking land for settlers, and trying to assimilate tribes into society, all in violation of treaties. Nothing is new.

These failures led to the protests on the 1960’s and 1970’s. The tribal people wanted control over their land and its resources, they wanted to be recognized as tribes and they wanted their land back. A tribunal was set up and Treaty claims have been in process for decades with compensation, land return and fairer treatment of the tribes as the goal. It is a slow process, but it seems to be working.