For years I joked that I was going to move to New Zealand and help the Maori. Well, I moved to New Zealand and I have been helping the Maori. I am not qualified to be an attorney in New Zealand and I certainly don’t want to be. I am fine not working thank you. But somehow, I was sucked into helping with a case for a tribe located in a nearby town.

New Zealand’s founding document is the agreement known as the Treaty of Waitangi. Signed in 1846, the British Crown and the Native inhabitants, the Maori agreed that the Crown was there for good but the Maori would be left alone. To summarize, and this is a very unnuanced statement, this treaty gave the Crown the right to exercise sovereign rule over New Zealand with the proviso that the Maori would continue to have self-government over their own tribes. The problem is that the Maori, without really understanding it, gave away their land title and they gave the Crown the right to govern the country. I say “without understanding” because, as was true of all indigenous communities, the Maori concept of ownership and authority over land and the British understanding of those concepts were two very different things. As happened in any country that purported to engage in sincere treaty agreements, the ensuing settlement of Europeans onto indigenous land resulted in non-native dominance and the native population decimation.

New Zealand has sought to make some amends for the terrible history here and part if it is the Waitangi Tribunal—an entity where Maori tribes or iwi can make claims for lost land, breaches of the Treaty, and other harms caused by settlement and exploitation. The Tribunal then makes a report as to whether the claim is valid. The Tribunal can also be asked to look at remedies which can be recommended to the Crown. In some circumstances, the Tribunal can issue orders but that seems to be a last resort. Their goal is settlement of claims once they have been aired and examined.

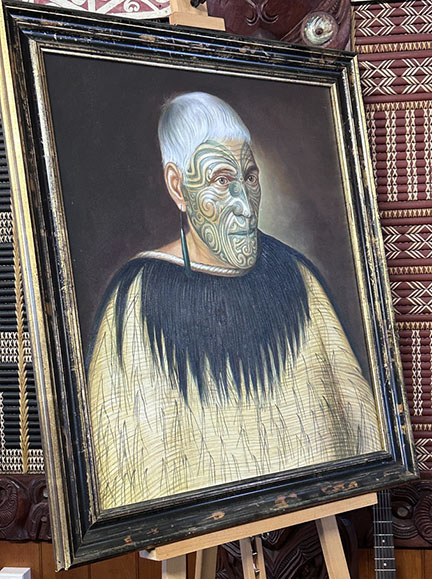

So how did I get involved? I was reading the local paper–they actually still have local newspapers here–and I saw a notice that a Tribunal hearing was going to take place nearby. I decided it might be fun to go and see what goes on. That is one of my traits. I really like to see what goes on. One early morning I set out for the marae, which is the tribe’s meeting house and communal center, to attend the hearing. I stopped to ask if it would be okay for me, not a tribal member and not a Maori, to attend the hearing inside the marae. Everyone said it was fine. I took off my shoes and entered. The marae was crowded with members of the iwi sitting on benches shoulder to shoulder. People were greeting each other with kisses on the cheek between women and the nose greeting or hongi with men. The space was decorated with carvings of Maori gods and painted in a scroll design known askōwhaiwhai.

I squeezed onto a bench in the back and watched the show. There were legal representatives of the New Zealand Government or Crown, three judges, and some experts. The claimants read their written testimony into the record and then answered questions presented by the Crown and the panel. It was not exciting, but hearings rarely are unless you are completely absorbed in the issue.

But there was one aspect of the hearing that was delightful. After testimony, and at breaks, the tribal members sang songs. It is often said that a day is court at least allows a person to be heard. By singing, they were making their voices heard. Everyone stood and clapped and sang full throated as if they were a church choir. I don’t know what the songs were about since they were singing in Maori. It struck me that they were singing of being together with a hopeful plea to the Gods to render a decision in their favor. Imagine this happening in a U.S. court of any kind–a family or group of claimants breaking out into song at the end of testimony. Order in the Court! would be the cry. Setting aside where this was happening, gosh, we as a culture have lost so much having moved away from informal sing alongs.

The hearing was stopped for tea at around 11a.m. and then again for lunch at around 12:30. At the break, I introduced myself to the attorney representing the claiming tribe explaining that I had worked in Indian law in the United States, particularly a land claim. The attorney nodded politely until I mentioned the land claim. Then she sprang to attention, her eyes focused on me. She asked for my number and said she would contact me. I did not think anything of it and assumed that maybe we would have lunch some time.

About a week later I received a call from the attorney. She asked if I could come to her office for a meeting. She wanted to discuss the claims with me. I agreed to come by. I learned that she was desperate for help because some attorneys she had working for her had gone off to other jobs leaving her short staffed. She figured that with my experience I would not need much in the way of education.

The assignment was to read three expert reports, amounting to hundreds of pages of text, absorb it and wring out of it a coherent factual narrative to support the claim for land and damages. Oh, and I had a week to do it. One week to learn everything I could about the history of a claim, and regurgitate it into a witness statement. By the time I learned the deadline, it was too late to say, I pass. In any case, I am pretty sure she was not going to take no for an answer. I took the reports and drove home.

I have not really worked hard in about two years and I had to absolutely crash into the texts, reading as fast as I could and making judgments about what was or was not important. I had a set of guidelines as to which facts were necessary, so I had some clue as to what I was looking for. But what made it harder was the use of Maori words in the text. I do not speak Maori, not even a little. But here were expert reports filled with Maori concepts that are embedded in the Maori language. So I did what any normal person would do. I located a Maori dictionary on the internet and started translating the document. In this project, I was not only learning the history of the area I live in—the Maori tribes who occupied the area, the uses of the land and river the actions of the British to take it all away—I was also learning Maori.

Even more challenging, once I had read the reports, I had to write a factual statement to be delivered by a Maori witness that had to include the concepts and the language. I made a cheat sheet of recurring words and forced my brain to incorporate the concepts into the narrative.

I have not busted my butt like that for a while and honestly, I did not like it. I had forgotten what it is like to have to sit at a desk and get something done on a deadline. I am anti-deadline at this point in my life. I am all about fluidity and serendipity. Whatever comes along. And if something comes along and I can’t take advantage of it because I have to sit at a desk and be responsible, oh, that just makes me irritated.

On the other hand, I was helping a Maori tribe get some vindication for the wrongful actions of the Brits oh so long ago. No surprise that they took Maori land by settlement and the assumption that the land title ultimately belonged to the conqueror. Maori fishing rights were significantly impacted by damages to the river and streams from which they gathered their food. It is the same old story no matter the country.

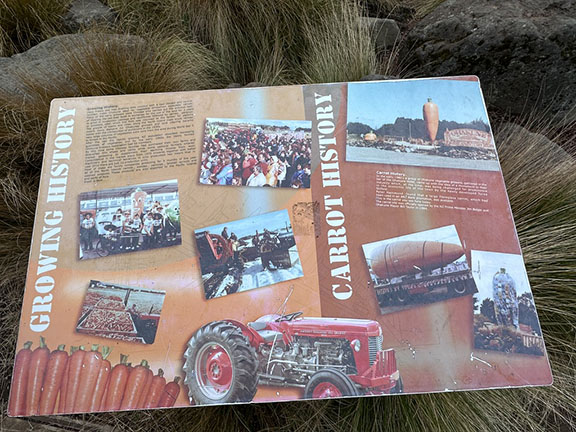

So I pushed on and pumped out a draft statement in four days. I explained that the area was conquered by a mighty chief who brought his people from the north to settle along the river. I explained that eel was a very important part of the Maori diet but that river dredging had damaged the fishery. I explained that flax, which grows everywhere here, was an important trading good. The Europeans wanted it for linen. Gathering flax was done communally and it was important to the tribe’s cohesion. But it soon became an industry with the Europeans, and the Tribe lost that connection to the plant and to each other.

I learned a lot and I found it very interesting. I think it met the goal of establishing the Tribe’s connection to the land and river. About a month later, I attended the hearing at which the witness read the statement into the record. I was happy I could get it done for them and I hope they win something.

Am I finished with the Maori claim work? I have no idea.